Learn from your past to get fitter and faster

When I start working with someone new I always spend some time learning about things they have done so that I understand what has worked for them in the past and what hasn’t worked so well. I thought it would be useful to explain how I go about this so that other people can learn from my experiences.

So, how do you learn from your past to get fitter and faster? Look at hard data first, heart rate, power, pace and any associated comments, don’t rely on memory at least initially. See how your training data relates to when you were performing better or worse. Look at your personal calendar/diary to see whether any events correlate with your training data. Ask friends and family what relevant things they remember. Make some notes and use these to guide your goals and training.

You can learn an amazing amount from the past, even if you don’t have any formal records such as a training diary. It is worth spending some time on this because information can come from many sources, even spending some time reviewing old photographs, Instagram or Facebook can yield interesting information.

Learning from the past

It is best to look at the most specific, recorded data first so that you are as objective as possible. These data could be heart rate, power, speed, pace, event times, bodyweight, resting heart rate, HRV, etc that have been recorded and uploaded to an online platform such as Garmin Connect, Suunto Movescount, Polar, TrainingPeaks, Strava or any of the multitude of other apps available nowadays. Most of these tools allow you to plot graphs of data over specific periods so look at the big picture and see what trends or changes are apparent. During this process, it is worth comparing data from previous years if you have any, to see how you are improving, or perhaps not improving and in what areas are you getting better or not improving so much.

After this, you can be less specific and look to other sources such as your diary, which may show certain events that correlate with the training information. Social media, photographs, ask friends and family what they remember and start to add some more subjective understanding to what has happened.

Make this an iterative process, so that once you have some information you think may be important, check to see whether it relates to other information to try to figure out whether you can identify a cause that you can either repeat for good effect or avoid if appropriate. Don’t worry too much if you can’t figure something out; we are all human and don’t always respond in predictable ways so it could be just a good or bad day. You might also find that a few nights sleep give you some insight as your brain works on the problem subconsciously.

Training data

Start by looking at the overall picture. Good ways to do this are the performance manager in TrainingPeaks or the breakdown of your training hours in Strava, or similar data from other applications.

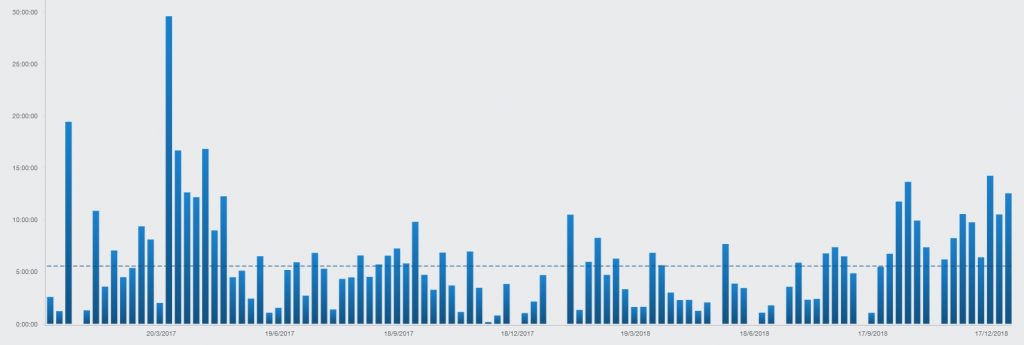

The figure shows a breakdown of weekly training hours over a 2 year period, giving a nice insight into history, what might be possible in terms of volume and periods of down time.

The peak in April 2017 was a training camp in Mallorca and the downtimes have been periods when work has got in the way.

Hopefully you can see how looking at this sort of information can give a lot of insight into the past and provide a good basis to move forward, avoiding past mistakes and building on things that have worked well. For this athlete, there is certainly a lot to be said for going on a warm weather camp to get the season off to a good start.

Heart rate data

Once you have some insight into the overall ups and downs, you can look in more detail at what was happening at the time. If you recorded your heart rate during training, or other data such as pace or power, you can look at how much time you spent in the various training zones during different periods of time.

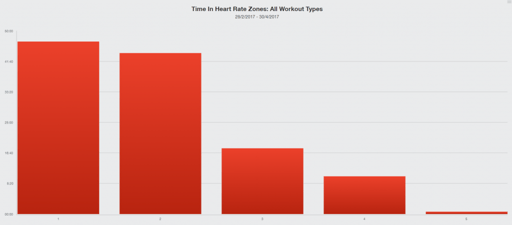

Going back to the example above, you can see that during the Mallorca training camp, the

Mallorca – March-April 2017

You can see from the heart rate based training profiles that when in Mallorca, the training was mostly in zones 1 and 2. This is perfect for a period of high volume training that is designed to build a base and is a positive thing.

After this period, the athlete had a great base to move forward from. We can also see that quite a large volume is tolerable for a period of time and this may prove a valuable approach in the future.

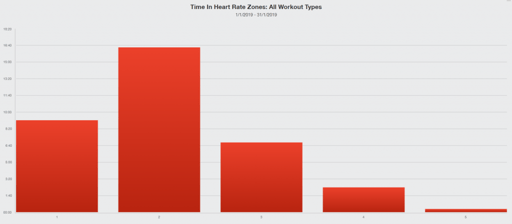

January 2019

In this graph you can see that the training was more intense, with less time in zone 1 but there was also less volume, as you may be able to see from the durations on the left hand axis. This was a period of normal training around work and things were going well.

Fitness was building nicely with some tempo work whilst maintaining good volume.

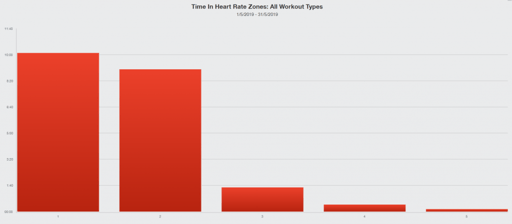

May 2019

Things started to go wrong for the athlete in April and in May of 2019 you can see that the there was less time in the higher intensity zones 3 and 4 as well as a lot less volume.

Although this was the case during the training camp described previously, the training volume is substantially reduced and it would have been expected to have a progression from January, which didn’t happen.

This may have been a sign of over training syndrome but after some investigation, it was found that the athlete was in fact ill and therefore necessarily had to back off further to recover. This can be seen in the overall hourly profile that we talked about earlier.

You can review pace and power data in a similar way.

Detective work

As you can see, it takes a bit of detective work and combining all available data, which can then be reviewed against comments and performances to build a picture of what might be good and not so good.

Think about where you might have posted useful information

Once you have reviewed your training data it is a good idea to consider other sources of information that might help you learn about yourself.

Don’t rely on memory – memories change with time

Don’t rely on your memory of what happened or how much you were able to do a few years ago. Memories change with time and we can also change them more if we get a misconception into our heads.

I can share a personal example. When I was younger I injured my ankle, because I didn’t know what I was doing and I was keen to get back into my running I didn’t look after it properly and the problem has stuck with me for the last 30 years. So, as an aside: make sure you recover properly from injuries. Because I knew I had struggled to train with the injury I had warped my memory to thinking I had done all my best running before the injury and the injury had led to reduced performance. However, when I reviewed my training diaries years later, I found that my biggest mileage training had been after the injury, as had perhaps my best performances. The injury hadn’t reduced my ability to train hard but one thing I hadn’t realised is that it had hampered my ability to run on rough terrain, leading to worse performances in some races. Review of my recorded data showed that the injury had caused some problems but still allowed me to perform better in other events, something that I could have used more effectively to target more appropriate events.

Look over older data if you have it

You can see from the example I just referred to that looking over old information in the form of training diaries or other information can uncover very useful information that you can learn from.

Think about the distant past

You can also learn a lot about yourself by thinking about the distant past, even as far back as when you were at school. For example, were you good at team sports where there was a lot of skill and sprinting involved or were you more of a loaner, enjoying more solitary activities. This might give you some insight into why you enjoy certain aspects of your sports and find others difficult.

Think about your personality – how can you learn from it

If you are an introvert, you may like training on your own and be attracted to sports where you enter a private world of focus. This may give you some insight into how to approach your events, focusing internally on your own processes without worrying about the outcome. You may prefer to do a lot of your training on your own and just spend time your down time with your friends rather than doing group sessions that you may find more stressful than effective.

If you are an extrovert, you may be more comfortable with direct competition and therefore having a partially external focus as you aim to beat certain of your competitors may help. you may also find that doing training sessions with others is more effective and enjoyable and find it hard to motivate yourself to go out training on your own.

Obviously these ideas are very much generalisations but I am putting them forward as much to stimulate thought than to state hard and fast rules.

Other questions you might like to ask are:

- Think about what training sessions you like and which you don’t like

- Do you prefer racing or training?

- Do you like to train alone or in a group? Do you train harder on your own or in a group?

- When in a group, do you work harder because you don’t want to slow everyone down or because you are competitive?

Compare your performances to get an idea of strengths and weaknesses

To understand your strengths and weaknesses you need to compare your data with some sort of baseline. You can do this by looking at the results of events you have done, for example, are you better at hilly events or flat events, road events or off-road events, events requiring more technical skill an agility, etc.

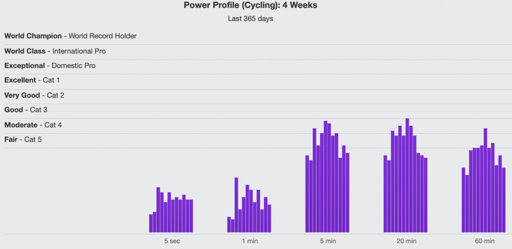

You can also compare your performances with normative data that is now available in some of the apps. For example, if you have power data you can look at the charts in TrainingPeaks and see how you compare to the norms, as well as look at your improvement over time.

You can learn two things from the chart to the left. Firstly that the athlete is more endurance based than they are a sprinter because the powers around 5 and 20 minutes are much better than those at 5 seconds and 1 minute. Also that they were improving quite nicely for a period of time and then things started to drop off, you can see this as the bars go up towards the Cat 3 area in places and then drop off.

You have to be a bit careful with general data like these because the results depend on the type of training you have been doing. For example the 60 minute powers in the figure aren’t as high as the 5 and 20 minute powers but it is likely that this is because the athlete hasn’t done any unbroken 60 minute efforts. This may also be the case regarding shorter efforts.

Using the information to make a plan

Once you have all the data, you can use it to develop your plan for your event. You can do this by identifying the requirements of your goal event and comparing these with your findings from your analyses and your current state of fitness. This is beyond the scope of this article, but you can find lots of information about how to develop a plan in our ebook.

By way of an example and following a classic approach to the training year, whereby you build endurance and then more into higher intensity work. The athlete we have used for our example may be advised to do a block of high volume, low intensity endurance training in December or January to build a base, perhaps this could incorporate some time at a warm weather training base. After some recovery from the volume, the athlete would build intensity in a similar way to the January 2019 data, hopefully avoiding overtraining or illness due to the strong base and move forward into the completion season with more specific, high intensity work.

Related questions

How much training is too much? This is a big question that is asked many times at all levels of sport and isn’t well answered because humans are so complex. The answer is that what is too much training varies between individuals and for the same individual at different times, depending on the amount of training volume, the fitness and particularly exernal stresses that may be emotional, due to family or environmental such as poor weather. The best way to spot whether you are doing too much is to keep a track of how you feel each day along with more objective measures like HRV, sleep duration and quality, and resting heart rate along with your weight. If you experience a change that lasts for a few days then something could well be going wrong and you should take action, usually by resting.

How much recovery should I take between my last event and starting training for the next one? Again, this depends on the event but in general, you should rest completely until you start feeling like going out for some easy exercise (not training). At this point, depending on the event or season you have had, you might feel you can exercise easily but you don’t have the power to go faster or push hard. This is okay and quite normal so take your time. You will get back to where you want to be but don’t rush. Typically, athletes rest between 2 weeks and 2 months between the end of one season and the start of another.

Good luck and let us know if we can help

August 21, 2019

Comments