5 Reasons you should train with power

Power meters have been around for over a decade now and are becoming increasingly affordable, particularly if you look to the second hand market. There are also many affordable alternatives to buying and fitting a power meter on your bike such as using a Wattike at the gym or a smart trainer. Even basic trainers can be calibrated to give power output when combined with Apps such as Zwift, TrainerRoad, etc.

I thought it would be useful to reflect on why I think training with power is a worthwhile investment. In fact, in many cases, I think it could be better to spend less on a bike and save enough to buy a power meter if you are serious about getting the best out of yourself.

Power is a direct measure of how hard you are working at any given time

Measuring your power gives an instantaneous indication of how hard you are working. Unlike heart rate, which takes time to respond when you put an effort in, your power output changes immediately.

Why is this important?

When you are out cycling, there are many small changes in your effort such as going up small hills, accelerating out of corners or pulling away from road junctions. These short efforts wouldn’t be long enough to result in a change in heart rate but they all generate fatigue and can help you have a better understanding of your training volume or learn how to ride more efficiently.

Power gives you a more accurate measurement of how much work you have done

Because power is measured directly, it accounts for variables such as changes in terrain, tyres, weather conditions, aerodynamics the weight of your bike and your kit, it gives a much better measurement of how much you have done than distance or duration combined with heart rate. In fact, the only error in the calculation is how accurate your power meter is because power multiplied by duration is how much work you have done. Since power meters are generally regarded to accurate to less than 5% and some smart trainers such as Tacx Neo 2 quoting accuracies of less than 1%, well within any range of acceptability for almost all training and racing purposes.

Measuring the work you have done in any training session and adding this up each week, month, year, etc, helps make training progressive and also helps you learn what training volume works best for you at any time of the year or as you approach any given event.

Unfortunately this aspect of measurement isn’t perfect but it is better than other options, particularly if using historical data to understand similar, repeatable circumstances.

The reason that there is some ‘art’ mixed in with the science is that the variability of your training is important, and while this can be accurately measured, the impact this has on each individual isn’t the same.

“What about heart rate?” I hear you say! Well, as I discussed in point 1., power is a much better way of measuring variability than heart rate and heart rate is similarly restricted by the need to understand the impact of variability.

Why is variability important?

The relationship between the level of effort you work at and the amount of fatigue created isn’t linear, if it were, we could just use average power or average heart rate multiplied by the duration of a workout to give the training volume.

What this means is that it is much easier to ride easily for 1 hour than it is to ride twice as hard for half the time (half an hour) and much harder to ride 4 times as hard for quarter of an hour. This is due to our physiologies, which are all different.

Some people are good at doing short sprints but get tired doing longer even paced efforts and others are the opposite. Whilst it is possible to train to get better at each part of the spectrum, there is a significant part that is due to the underlying physiology we were born with.

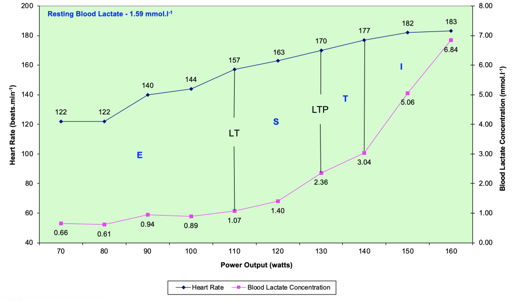

The graph below shows the relationship between power, heart rate and blood lactate concentration. You can see that lactate levels don’t change much as power increases at lower powers but rise increasingly rapidly at higher powers. Once the lactate concentration in your muscles gets to a certain level you have to stop or slow down because your body can’t get rid of the lactate fast enough to maintain a balanced condition. This is the point you feel your muscles burning, often on hills or if you are trying to keep up with someone who is faster.

You can see from the graph that the hard, higher power, efforts are much more damaging (i.e. create proportionally much higher lactate concentration) than the longer less hard efforts. This means that if you do a ride of 1 hour at a power of say 200 Watts, it is easier than if you did a ride that is 40 minutes at 150 Watts but has several efforts of 300 Watts, totalling 20 minutes, although both have an average power of 200 Watts.

Using this variability, there are several ways to estimate the impact of any given workout by accounting for the durations at various powers relative to what is known as the functional threshold power (FTP). Your FTP is the power you can sustain for a reasonably long period of time, usually between 40 and 70 minutes and having a reasonable estimate of this is important to get a good idea of many metrics when working with power data. Here is an article that explains how to calculate your FTP and other thresholds that can be useful.

The most common and increasingly accepted way of calculating the impact of any ride is known as Training Stress Score (TSS). The TSS from each workout can be added to give a TSS for longer periods, such as a week, month or longer. This can be used for both planning and measuring training and works effectively. However, it is only a measurement of your training stress and doesn’t account for other factors such as life stresses at work or home, illness, not sleeping enough, etc., so be careful and take account of objective measures such as mood, muscle soreness, etc, as well.

Power is a very effective way of pacing your events

By practicing riding at certain powers on different features, such as uphills, downhills, flat, etc, you can learn what level of effort is sustainable for the durations of your events.

For time trials and the bike legs of triathlons, where the course is known and you can clearly define what you need to do, you can use sophisticated pacing tools such as Best Bike Split to calculate the power you should be working at during each section of the course. By planning this according to your fitness, strengths and weaknesses you can optimise your performance.

For longer events, where you may not be sure of the route, you will be riding on unpredictable or unknown surfaces, perhaps off-road, or over several days where you are unsure of the weather, you can develop rules of thumb that give you the best chance of using your energy optimally.

In general, it is more effective to ride harder when it is harder, that is ride uphills harder than downhills and flat sections at an intermediate level of effort.

If you are doing long events and particularly multi-day events such as self supported, bike packing events or stage races, your heart rate won’t be a good guide. In fact, your heart rate is affected by heat, altitude, hydration and many other factors that can make it difficult to use for accurate pacing.

With power you can use your longer training rides and power duration data to understand what powers you can sustain for certain periods of time, how long it takes you to recover from certain rides or efforts and therefore set ranges for uphills, downhills and flatter sections that you can use in your events. You can then test these ranges in lower key events to see how well they work and make adjustments as needed.

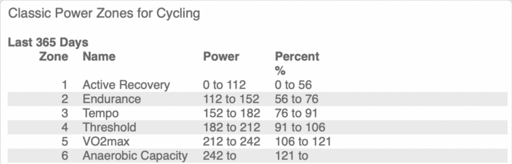

A good starting point for these power ranges can be your training zones. I like to use the Andy Coggan zones that you can calculate in TrainingPeaks for endurance based training because they are designed for cycling, relatively simple to understand and I have found the 5 zones to be adequate for most needs. Here are the zones based on a FTP of 200 Watts, remember to calculate your own zones, the figure is for illustration and your zones could be significantly different.

As a starting point, for events that are at the limit of your endurance, I would try riding uphills in zone 3 (Tempo), flat sections in zone 2 (Endurance) and use downhills for recoveries. Shorter events where you know you are comfortable with the duration and you are aiming to go faster can be at higher levels of effort. It is all personal, so use this as a guide and make changes to suit your fitness and goals.

Bear in mind that as you get fitter, your FTP and therefore your zones will get higher, so you need to keep testing and revising the numbers.

Power helps you identify your strengths and weaknesses

Modern technology allows you to measure and record your power every second of your ride, which in turn allows you to generate a profile of your best powers over a spectrum of durations. By testing regularly, you can make sure this power-duration profile is accurate and up to date.

Combining this information with the demands of your event gives you tremendous insight into what you need to do to get better and where to focus your training.

For example, if you are wanting to race cyclocross or criteriums you will need to be able to work hard for 30 minutes to an hour with variable levels of effort because there are lots of times when you slow down and speed up. You can ride some races with your power meter and compare the results with where you found the race harder or easier. For example if your found the start hard and couldn’t keep up, but then found you pulled through when things settled down although having to contend with working through the field, you may need to work on your higher short term powers and just maintain your FTP. If on the other hand you are generally struggling with the pace throughout the event you may need to raise your FTP and not worry so much about the shorter term powers.

For longer, gravel races, sportive and ultra-endurance events, it is a bit different, you will want to build up the average speed that you can ride at for a very long time without getting significantly more fatigued. You do this in two ways, increasing your FTP and increasing your endurance to ride for a long time. Most people can ride the distance, given enough time, so what makes the difference is the pace. You can ride at a higher pace by raising your FTP and your ability to burn fat as an energy source at higher intensities. You can raise your FTP by doing harder efforts a bit below and a bit above your FTP and you improve your ability to burn fat as an energy source by riding for a long time at an easy level of effort – zones 1 and 2. I discuss some sessions you can do to build your FTP in the article SE A WATTBIKE TO GET FASTER AT LONG DISTANCE CYCLING EVENTS’ as well as how you can structure your week to be most efficient with your time.

Power helps you design train sessions that are consistent with your strengths and weaknesses

Following on from point 4, once you have identified your strengths and weaknesses so that you know where best to apply your effort, you can use the power-duration curve to design workouts that stress your system to improve.

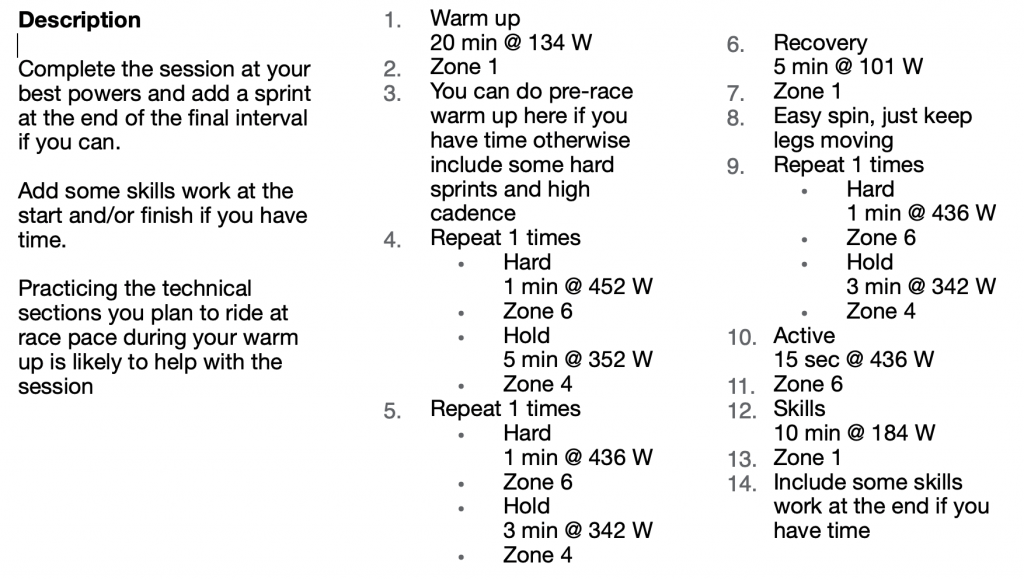

Going back to our cyclocross, or perhaps a cross country mountain bike event where the starts are important to avoid getting stuck behind the field. It is important to be able to start fast and recover to get into your rhythm as quickly as possible. If you go too hard at the start you are at risk of blowing up but if you don’t go hard enough you are likely to be stuck behind slower riders, perhaps the ones who have set off too fast and blown up. These fast starts are a case of building sufficient anaerobic capacity to cope with a fast start but combining it with a reasonable FTP to have a good sustainable power.

One session I have found to be really effective is one I call hard starts, I have used this with both cyclocross and mountain bikers to good effect and it builds both anaerobic capacity, VO2max and as a result lifts FTP, particularly if combined with some longer efforts. To build anaerobic capacity it is best to do efforts that are as hard as you can to the point where you have to slow down or stop. You want to deplete your anaerobic reserve so that your body knows to build it up stronger to be able to cope better next time.

Here is the hard starts session:

For longer events it is also important to raise FTP but less important to worry about anaerobic capacity. As discussed on point 4., building FTP is best done with sessions a little above and a little below FTP, if you are working above FTP you will still be working anaerobically but your body will raise your anaerobic threshold (roughly the same as FTP) to allow you to cope better next time it is in the same situation.

These sessions above FTP can be done at your VO2max power (roughly as hard as you can go for one effort of around 6 minutes). You can then do sets of efforts with durations of from 30s to 5 minutes with the same durations recoveries until you can’t do any more. Typically this will be 10 to 20 minutes of hard work, so 4 to 8 x 5 minutes.

If you are working a bit below FTP you can do efforts with shorter recoveries. A really good session is 3 or 4 x 8 minutes with 2 minutes recoveries. These should be at 90 to 95% of your FTP and again, do them until you can’t do another one.

That’s it – it is definitely worth working with power, whether that is using a Wattbike at the gym, a turbo trainer or of course, the best option is a power meter on your bike or bikes.

Good luck, have fun, don’t get hung up on details and get in touch if we can help.

Related questions

What is the best power meter? Well, it is a bit cliched but the best power meter is the one you have access to. Don’t get too hung up on what is most accurate or which one measures what and how. Look for the most convenient option for you and go with that, they are all pretty good nowadays. If you have several bikes then pedals can be good, if you have limited budget but gym membership, see if there is something at the gym.

Can I use a power meter to calculate how many calories I am using? This might not seem like a good question to associate with an article on detailed training methods but it is relevant. Nobody wants to be overweight or worse, to not get enough of the right nutrition or calories. Most applications now make an estimate of how many calories you are using but this may be based on heart rate or another algorithm that is hard to verify. A good rule of thumb is to take the energy you have output in kilojoules (kJ) and that gives a roughly direct idea of how many calories you have used – it works because your body isn’t 100% efficient in converting food energy to cycling energy and the efficiency factor is coincidentally similar. Try this and if it isn’t quite right (you lose or gain weight) give it a tweak until it works.

January 21, 2020

Comments