Why do I need interval training to get faster?

Last week, I wrote an article about how to set the intensity of your interval training sessions and made a video about why you need interval training to help you get faster, so I thought it would be a good idea to explain why you should be doing interval training in more detail, to help explain in more detail how it will help you to get faster at your running, cycling or swimming.

So, why do you need interval training to get faster? Interval training allows you to spend more time at higher intensities than your race pace than is possible with continuous hard efforts. By definition, your race pace is the fastest you can go for the duration of a race. By breaking your efforts into shorter blocks with recovery intervals you can work harder than your race pace for longer durations. This causes your body to react and get faster, so that you can race faster.

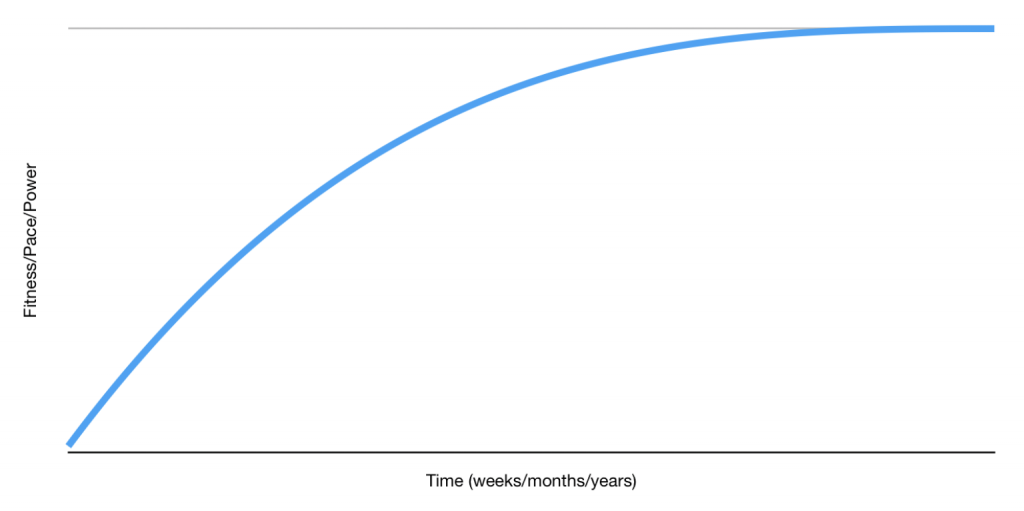

When you first start out in endurance sport, you get better by just getting out and doing your sport. Your cardiovascular system gets more efficient and you get used to going for longer, basically, both your efficiency and your stamina improve. After a while, your rate of improvement slows and then you find that sometimes you are slower and sometimes faster. This happens even if you train continuously and increase the amount of time you train for. You need to do something different to continue getting better.

Why do you stop getting faster if you only do continuous efforts?

The reason you stop improving is that your body gradually gets attuned to the training you are doing and even if you are doing regular races and events, you are able to cope with the intensities and durations.

It is commonly said that racing is the best training, which is only true to a certain extent and up to the point that you stop improving from your continuous sessions. As mentioned in the introduction, your race pace is the hardest and fastest you can go for the race duration. If you are running 5km in 20 minutes, you cannot go harder than that, or if you can, you aren’t trying hard enough. In cycling, if you are on the limit for the duration of your event, you are going as fast as you can for the given duration.

Because you need to work your body harder to get a stimulus that promotes the development of fitness, you can see that there is a limit to how hard you can work by doing continuous efforts and therefore you need to do something different to induce further development.

You can see this slowing of improvement in the graph.

If you are working with power or pace in your training, this curve generally has a correlation with your Functional Threshold Power or Functional Threshold Pace (FTP).

If your event is between 30 minutes and an hour, your ‘race pace’ will be very close to your FTP, if the event is less than an 30 minutes, it may be faster and if more than an hour, you will have to go slower than your FTP. However, it is fair to say that if you are taking part in events of longer than 15 minutes and less than 2 hours, there will be a strong correlation between your performance and your FTP.

For longer events that last several hours or even several days, there are many other factors at play but increasing your FTP is still likely to help you get faster and consequently doing some interval training is usually worthwhile. Having a higher FTP will increase your overall average speed and your ability to cope with harder efforts such as getting up hills.

There are two ways to improve FTP, one is by longer continuous efforts at or a little below your FTP and the other is by doing efforts that are harder than FTP. Once you have exhausted the effectiveness of building your FTP by continuous efforts, as described earlier, you need to do something different and this is where interval training comes in.

Why interval training?

By doing shorter efforts, you can work at a higher intensity (higher pace or power), therefore stimulating your ability to go faster. Because our bodies react and adapt to the stresses imposed on them, you will adapt to the faster pace and therefore become better at it.

Doing this repeatedly, with recovery periods between efforts, in the form of interval training allows you to spend more time at the higher intensity and provides a much stronger stimulus than just doing one continuous effort.

The resulting adaptation manifests itself in your body becoming more efficient and improving your performance at the target intensity. Using this method to work on your aerobic fitness to improve your FTP or you pace/power at your VO2max results in improved performance up to and beyond your FTP, meaning you are faster at your chosen event, whether that be 15 minutes or several days in duration.

What are good interval sessions to get you faster?

This can be a much harder question to answer if you are aiming to make very refined improvements at elite level, in which case it makes sense to work with a coach who understands your needs and can add objective analytical details to your training plan as well as monitor the outcomes. However, there are very few people that need this level of detail.

The best approach is to look towards the intensity of effort you want to improve. I wrote an article about how to use a structured model called the 5 pace system to design interval sessions to meet your needs, you might find that worth reading after you finish here. The title refers to cycling but it is just as good for running and in fact, the original 5 pace system was designed for runners.

The idea is that you do a mixture of paces with an emphasis on your main goals. For example, if you want to improve your FTP, you would prioritise intervals at intensities at your 15 minute pace and also at your 5 minute pace. Your 15 minute pace is a bit above your FTP and your 5 minute pace is roughly the pace or power that you can perform at VO2max.

Typical sessions to target these areas would be:

- 15 minute pace: 3 or 4 x 8 minutes with 2 minutes recoveries;

- 5 minute pace: 4 to 8 x 2 minutes with 2 minutes recoveries.

Doing too much interval training can be bad!

Doing too much of anything is a bad thing, by definition.

Higher intensity training is a lot more tiring than lower intensity training, so you need to be careful.

As a general rule, it is better to do less than more because some harder training will make you fitter but too much will make you tired to the extent you have to slow down or it could make you ill. The lesson here is be careful and build up slowly.

How to get started with interval training

I like to work with a weekly structure to help keep control of things. Scheduling interval training on Tuesday or Wednesday and having one session each week is a good approach.

With intervals, the intensity is the most important thing, not how many you do or how much time you are training for. The aim is to work at a higher intensity so that you get faster, if you are too tired to do that effectively, you will just get tired and probably slower.

Secondly, you need to work out how long to make each hard effort, how much recovery between efforts and how many to do. You can use the 5 pace system, as referred to earlier or you can figure things out for yourself.

Fortunately, it doesn’t matter too much how you mix up the harder efforts and recovery periods, it is the intensity of the effort and the total time you spend at that intensity that is important. In general, doing hard efforts of 1 to 8 minutes is good and adjust the recoveries so that you are ready to work again at the required intensity in your next hard effort. As you can imagine, it is easier if you have guidelines here.

General rules are that for your 15 minute pace efforts, you should have about a quarter of the duration of the effort as recovery. So if you do 1 minute efforts you get 15 seconds recoveries (hard!), 4 minutes efforts [1 minute recoveries], etc.

For your 5 minutes pace, go with the same duration of recovery as your effort, so 1 minute efforts [1 minute recoveries], etc.

For the number of efforts, it is a good idea to feel you could manage another 1 or 2 efforts at the end of your session but as you build your fitness, you should work up to, or close to, your limit. That is, you don’t feel you could do another hard effort.

A good rule of thumb is to do 10 to 20 minutes of hard effort for your 5 minutes pace and 20 to 35 minutes of hard effort for your 15 minutes pace.

There are no magic sessions

Hard work, time and consistency is what gets you fitter and faster.

A lot is written in the media about doing certain ‘magic’ sessions that are guaranteed to improve your performance over a given distance or event. In many cases, doing these sessions when combined appropriately with other training will lead to improvement but doing any session that progressively stresses your body to work harder and including the right amount of recovery between sessions will lead to improvement.

Keeping this in mind and not getting stressed about the details is worth doing. Worry about getting out training regularly, doing your best on any given day and you will almost certainly improve.

Related questions

Can I do my interval training using heart rate zones? Using a heart rate monitor is a really good way to do interval training when your efforts are longer than 2 minutes but not so good for shorter efforts because heart rate doesn’t go up immediately. In general, it is best to use pace, power or how you feel to guide your intervals. Heart rate is a great way to make sure you are recovering between efforts, if you find your heart rate is staying high for all of your recovery periods you may want to take longer recoveries.

Can I do interval training as part of my usual training routes? Yes, you can do interval training on any route as long as you can work hard during the harder efforts. This can be difficult on hilly routes where you may end up on a downhill for a hard effort, or if you are off road on difficult terrain. With a bit of thought, it isn’t difficult to find good routes to do your interval sessions on. You can also mix it up a bit with Fartlek – a subject for another article I think.

February 6, 2020

Comments