Why you need rest and recovery to get fitter and faster

You may have heard that fitness develops during recoveries and not during your workouts. Here is a bit more detail on the subject and the reasons why recovery is so important.

So, why is rest and recovery needed for you to get fitter and faster? Training is a process of stressing your body to create a response and then waiting for it to respond and build up stronger before stressing it a bit more so that it responds again. Each of these stress/response cycles is a step towards increased fitness with the response occurring during periods of recovery and adaptation. If you removed the response periods, you would be continually stressing your body and with no recovery you would get more and more tired. It is like trying to survive without sleep, forever! In simple terms, if you didn’t rest you would just get more and more tired until you had to stop or slow down, or in the worst cases, made yourself very ill to the extent you could take months or even years to recover.

Most people probably accept that some rest is required between workouts or blocks of workouts , such as hard training weeks, but what is harder to define and in many cases, accept, is how much. Understanding why rest is needed is the first step to determining how much you need..

Fitness and Fatigue

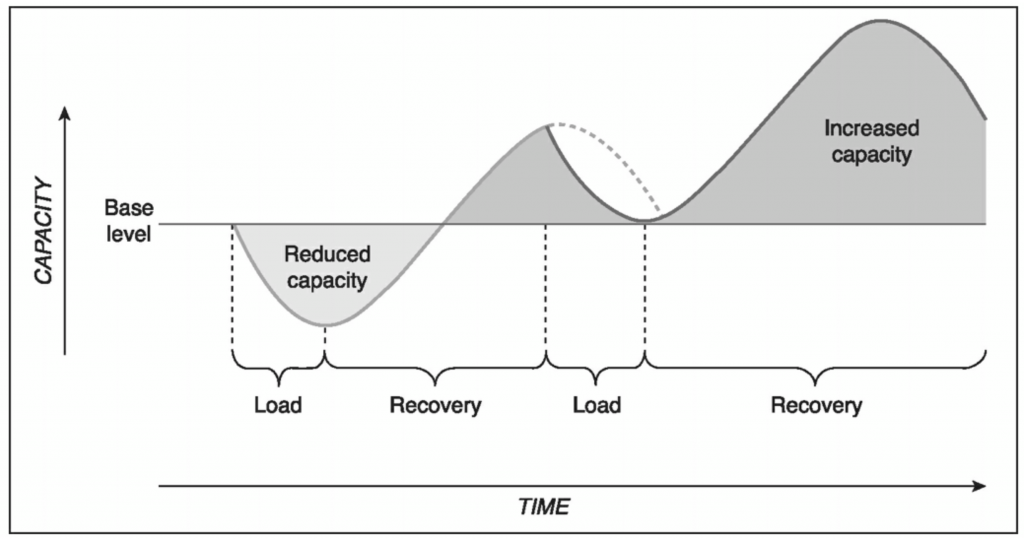

There are two ways of thinking about how workouts or blocks of training can cause fatigue and develop fitness. The most simple is to think of it as a wave, whereby each workout, represented by the Load in the figure, causes damage and then during the recovery period, Fitness, or Capacity, develops beyond the original base level. By doing another workout at the peak of the recovery curve, we can build Fitness/Capacity further with each load/recovery cycle.

Considering this idea further, it is easy to see that there are three directions this process could go.

Firstly, if each subsequent workout is delayed until the recovery curve drops to the base level, there is no long term gain in fitness, so it is necessary to train hard enough and often enough to create a response.

Secondly, as shown in both of the first two figures, by timing each workout to occur when the recovery curve is above the previous baseline, or ideally at the peak in the recovery curve, it is possible to build fitness in steps of each load/recovery cycle.

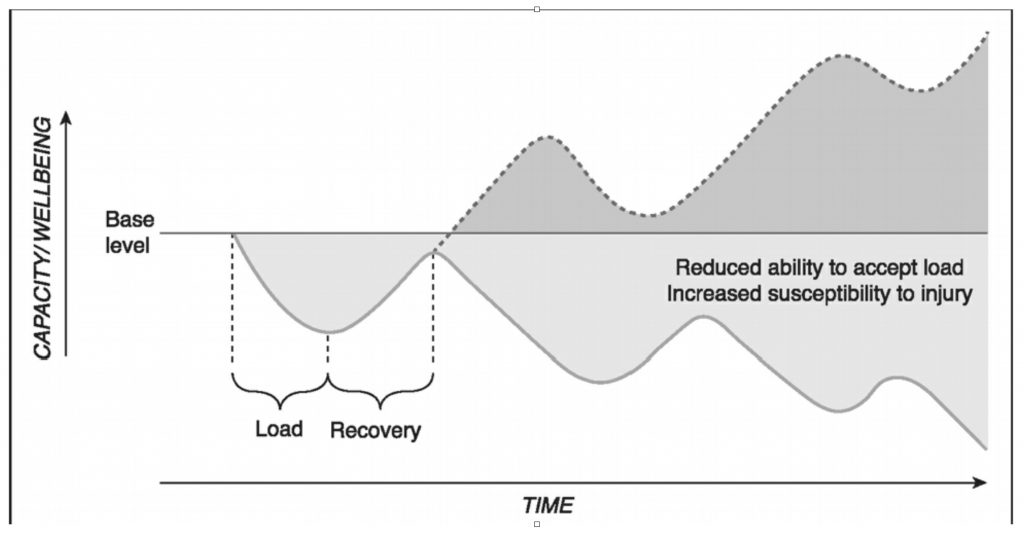

Thirdly, and what we want to avoid is that if workouts are performed before you have had sufficient recovery, before the recovery curve has returned to the baseline there is a reduction in Fitness, or Capacity to perform and Wellbeing.

By continuing to workout with insufficient recovery it is impossible to develop fitness effectively. If this cycle is continued longer term, the resulting fatigue can be very debilitating and can require months or years to recover to normal levels before you can start enjoying your sport again.

As you can see, it is a balancing act to plan workouts of suitable intensity to create a response and time these workouts after sufficient recovery has occurred.

Fortunately, there is a reasonable window of opportunity when the recovery curve is above the previous baseline and bearing in mind the risks of over training, it is easy to see (when thinking logically) that it is better to allow a little more recovery than too little.

In structured training plans, the load can represent either a single workout or a block of workouts that are designed to create a given response and followed by a period of recovery. Common protocols are 2 or 3 weeks of load followed by 1 week of recovery, with each week containing cycles of load and recovery within it.

Fitness, Fatigue and Form

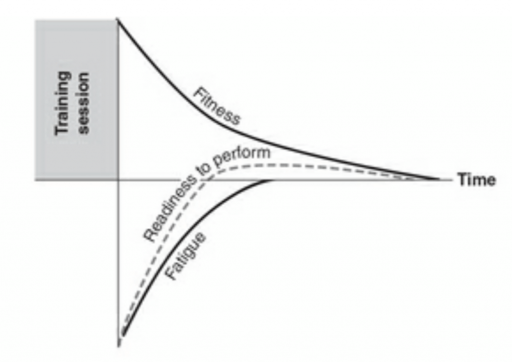

Taking this model a little further, we can look at things slightly differently and adopt the model attributed to Banister, et al. This model has been applied in various on-line applications including TrainingPeaks, where the terms are interchangeably used with Chronic Training Load (CTL, Fitness), Acute Training Load (ATL, Fatigue) and Training Stress Balance (TSB, Form). The units used for these metrics is Training Stress Score (TSS), which is derived from the accumulated intensity and duration of workouts that are planned or performed.

The model assumes that Fitness, which is the benefits of a given workout, are realised immediately but associated with Fatigue. The difference between Fitness and Fatigue represents the Readiness to perform, which is the Capacity/Wellbeing from our previous chart.

Fatigue is greater than Fitness but wears off faster than Fitness is retained, resulting in the Readiness to perform rising above the original baseline. This means that workouts that are performed after the Readiness to perform has risen above the original baseline and before the Fitness benefits of the workout have worn off can result in the stepwise development of fitness previously described.

This model has benefits over the previous model as it can be used to monitor the cumulative development of Fitness, accumulation of Fatigue and the Readiness to perform over time by adding the effects of various workouts and tuning the decay of the Fitness and Fatigue parameters.

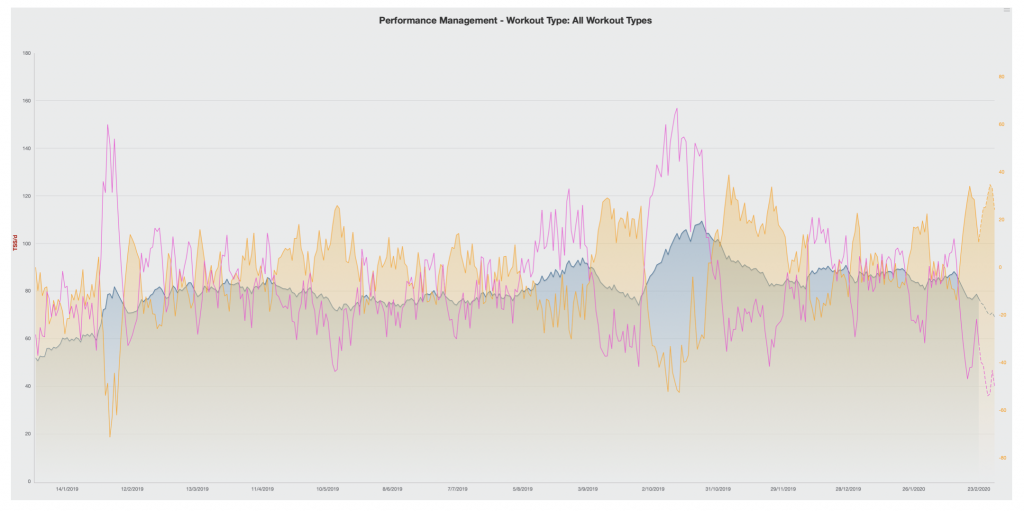

This can be seen in the screenshot from the TrainingPeaks dashboard of an athletes training over an extended period. The blue line with shading represents Fitness, the pink line is Fatigue and the yellow line with shading represents the Form.

The contributions of a given workout to Fitness and Fatigue are dependent on what is often denoted as Training Stress, which is a combination of the intensity and duration of the workout. These values can then be combined by making assumptions of how quickly Fitness wears off and how quickly recovery from fatigue takes place. This is different for everyone but with a little thought, this type of chart provides useful insights that can be generalised with care.

This model has some drawbacks, mostly in the way the respective parameters are calculated, but when carefully applied it can provide a useful basis for the development of training plans and monitoring of how things are going.

How much recovery?

There are no hard and fast rules about how much recovery is needed and how deeply fatigued a given athlete can become without this becoming excessive. The proportions of each of the Fatigue, Fitness and Readiness to perform values varies from person to person and even within the same individual at different times.

There are many different influences on how resilient anyone is to a given training load that include the Fitness, Fatigue and Form described above as well as other factors such as illness, life stress, weather conditions and many more things, some of which cannot be measured objectively.

During periods of high stress or illness, training cannot continue at the same level without things going wrong and it may be that a time of reduced training is necessary to avoid further illness or perhaps injury that could result in the need for a longer period of recuperation and sometimes complete rest in the case of overtraining syndrome.

How to determine how much recovery you need

The best way that I have found to determine how much recovery is needed, to quickly spot how things are going and make adjustments that bring you close to optimal training is to work with routines that form blocks of 1 to 2 weeks (microcycles) and 6 to 8 weeks (mesocycles) that are fitted into an overall plan for a season of a few months, a year or perhaps even a 4-year Olympic cycle (macrocycle).

The fundamental building block for me is one week, although I may vary the details of the sessions from week to week, the structure remains the same.

By doing similar things on the same days each week, it is much easier to understand how much recovery is needed after a given workout and therefore to know when one can plan the next workout for optimal fitness gains.

For most people, a structure that favours longer duration workouts at the weekends and shorter, more intense workouts during the week is most convenient and therefore effective.

People working from Monday to Friday often have limited time during these days and therefore shorter sessions are more suitable. On the weekend, longer sessions can be easier to fit in and even those that are not constrained by formal work hours often want to interact with those who are.

Therefore, if you do your longest workout on Sunday and want your first workout of the week to be a higher intensity session, you need to ensure you are adequately recovered to do the interval session at the required intensity. Looking back to our earlier discussion, you need to wait until your fatigue has dissipated to the extent that your Readiness to perform (Form) is appropriate for the given workout.

Similarly, you need to wait a sufficient time after your high intensity session before you are ready to perform another hard workout.

There is evidence to support doing low intensity workouts (<85% of Threshold Heart Rate, roughly <75% of maximum heart rate) between harder workouts. These workouts provide additional volume that stimulates fitness and don’t appear to have a significant detriment to the recovery process. However, what works for one person doesn’t always work for others, so use the structure to workout the best routine for yourself.

My experience of what works

I have found that most people can manage 2 or perhaps 3 high intensity workouts each week, with the remainder of the workouts carried out at lower intensity. Higher intensity workouts are things where levels of effort are at or above lactate threshold or Functional Threshold Power (FTP) and lower intensity workouts are performed at an endurance pace of typically less than 74% of threshold power (<85% of threshold heart rate).

Tempo sessions form the middle ground and I tend to see these as higher intensity workouts since they typically induce significant stress. There are arguments, particularly made famous by Stephen Seiler, that training sessions between lower intensity and FTP are best kept to a minimum because they do similar damage to high intensity workouts but have less benefit. As in many cases with training for sport, I think the reality is that it depends on your background, goals and current needs but it is worth bearing in mind that these sessions are hard and need adequate recovery.

It is now common place to work with a 3 or 4 week training cycle with 2 or 3 harder/build weeks where Fatigue is greater than Fitness and a recovery/adaptation week where the training load is designed to restore the balance between Fatigue and Fitness, increasing the Readiness to perform (Form).

In my experience, 3 hard weeks and 1 easy week is difficult to perform consistently due to both the psychological and physical demands. This is particularly the case for people with significant stresses outside their sport and so I tend to favour a 2 weeks on, 1 week off approach.

However, not everyone needs a full week of recovery and so 2 weeks on with a few easy days followed by some sort of test or race, and then a few easy days at the end of the week can be a very good structure to try.

A few warnings

- For both athletes and coaches, it is easy to be drawn into skipping the rest days and weeks in the search for increased fitness and performance but time and again this is shown to be counterproductive, so my advice is to take a break, even if you don’t feel like it at the time.

- Just by measuring the Fitness value, an element of competition is introduced that must be resisted. The name Fitness may imply the higher the better but this isn’t the case. There is an optimal level for everyone and for those limited in time, this is lower than it might be for those with more time. The optimum level at any given time is different as it is different for different athletes and understanding this is critical to optimum performance.

- Fitness, Fatigue and Form are just values to be thrown into the mix forming additional information to guide training. They are not absolute measures and should be considered only as a guide amongst other objective and subjective measures.

Sadly there is no magic number to aim for – I suppose if there were it would take some of the fun out of it!!

Good luck, have fun and remember it is perfect training that you need: Get fit not just tired!

Remember to enjoy it

Remember that you will ride more and probably faster if you are having fun. There is also significant evidence to suggest that you will recover faster and be at less risk of overtraining if you are enjoying what you do and taking control and ownership of your goals.

Related questions

Can what I eat help my recovery? Yes, eating the right things and staying properly hydrated both helps your recovery and your ability to work harder for longer. For optimum recovery you should eat a well balanced diet with the right balance of protein, carbohydrate and fats. After a workout, particularly a hard one, you should eat a carbohydrate rich snack that has some protein with it. This can be a recovery shake, snack bar or something you have made yourself. If you plan to eat within an hour of finishing your workout and don’t plan to do another hard training session within the next 24 hours, you can just eat normally and your recovery will stay on track.

Can heart rate variability help me know when I am recovered and ready to train again? Heart rate variability can be an effective tool, although in my experience, the recommendations on day to day readiness to perform are not the best guide as to whether to work hard. Observation of trends in heart rate variability can be very useful and I have found that these trends correlate well with developing fatigue or readiness to perform. A good way to look at trends is to consider a 7 day average and if this trends down for a few days it could be a sign that it is time to ease off and focus on recovery and looking after yourself. As with all things, spend some time observing the data and look for trends that work for you. There are general behaviours but you need to make it individual and specific to work for you.

February 6, 2020

Comments