How do I know if I’m too tired to train?

So some days you wake up and feel totally psyched to train, you can’t wait to thrash out some hard reps or blast it up the hills. Other days you feel so tired you can’t imagine training or doing faster than a slow walk. The weird thing is that on the good day the session can be absolutely awful and equally you can set off feeling tired and end up having a really good session. So how do we know if we are too tired to train?

Illness aside, if you feel tired but are generally healthy the best thing to do is to go out and have a go BUT if your heart rate is not responding or is going erratically high, or you are significantly off pace despite your best efforts, call it a day, run easy or rest, the session will be there another day. If this isn’t something that you feel you can achieve, the good news is there are other ways to track your levels of tiredness which will help you decide whether or not today is the day to train:

1) Resting Heart Rate

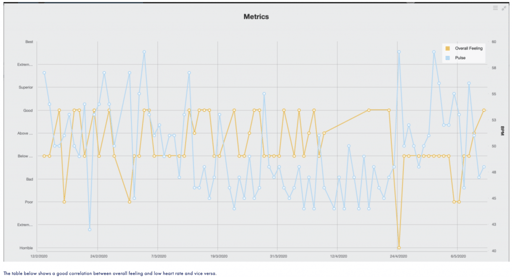

Checking your resting heart rate at the same time each day (morning just after you wake up is best) is a great way to track how you are physiologically. If you record it each day in your training diary you will be able to notice patterns and changes – unusually high readings and how they correlate with your overall feeling. If you use and application like TrainingPeaks, you could even collate it all into a nice chart like the one below. You can then cross check this with your training/racing performance.

2) Heart rate variability

Similar to resting heart rate but arguably more accurate, you could choose to measure your heart rate variability. There are several apps that can do this for you these days, the two most common that I have heard about amongst coaches are HRV4 Training and iThlete, both of which have free and subscription versions and will link in with other training apps so you can automatically get all your data in one place

Heart rate variability measures the difference in time between the beats of your heart which is governed by your stress response system coming from the hypothalamus (a part of your brain) and through the Automatic Nervous System (ANS). What this means is that measuring your heart rate variability is a good way of measuring your body’s stress response, and it takes account of physical and emotional stress as both are processed through the hypothalamus and ANS.

Each app works slightly differently, but a good rule of thumb is to choose either a finger pulsometer or heart rate chest strap above a camera/finger based system as these take more accurate readings. After collecting the readings for a few weeks you will have a baseline reading (all else being equal in that time period) which will then give you an idea of whether your heart rate variability is unusually high or low. In general, the higher the reading, the less stressed you are and the more ready you are for hard training.

Remember as with all apps and devices, they are only as good as the data you put in, so keeping it regularly updated and answering any supplementary questions honestly is the key to good feedback. As they work on a law of averages, if you do have a prolonged period of illness, this can create a new (and inaccurate) baseline, so it is worth holding in mind what you know to be normal for you rather than just taking the app at face value. If you are recording the readings each day, this will be easy to do.

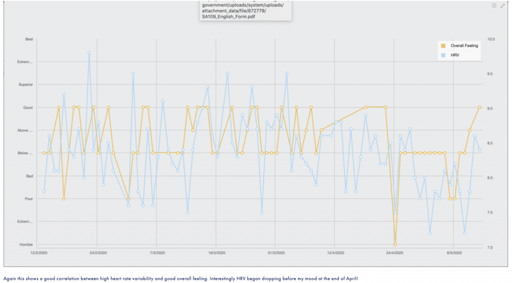

If you have linked the app to your usual training app, you can again track the data and correlate it with both training and overall feeling as below.

3) Subjective scoring.

For those of you who have less time and patience for gadgets and readings, there are still ways that you can assess your overall tiredness. Some common and good indicators that you may be bordering on over-trained and therefore need to back of a bit are:

Reduced sleep quality – poor quality sleep (that is outside your normal sleeping pattern) can be a good indicator that it’s time time have some easy days/rest days so that you can wind down, let your body relax and your muscles start to absorb training.

Muscle soreness – muscle soreness that is not linked to new training can also be a sign of reaching a point beyond healthy over-reaching and mean that you need time to let your muscles repair and come back stronger before engaging in more hard activity.

Fatigue levels – general fatigue levels get elevated when you need to rest, you will notice this in how groggy you feel, but also in other ways (I used to measure it against how tired I felt walking up the two flights of stairs to my old work office).

Grumpiness levels/Mood – when we get over-tired and over-trained we (or perhaps those around us) will notice a decrease in mood or an increase in grumpiness levels. This can also be expressed in our ability to handle set backs (I know I need to rest when spilling milk becomes a world tragedy!). If you notice you are feeling frequently over-whelmed, you are snapping at family/friends or generally feeling unusually grumpy with the world it might be time to take a break from training.

Motivation to train – there’s being a bit tired and there’s feeling like there’s no possible way you can manage the training session tonight. If you are bordering on the latter and can’t bear the thought of stepping out the door when you are usually happy to train this can be another good signal to take it easy.

Stress levels – As I have mentioned in my previous article, general stress can impact our ability to recover from hard training, so it’s worth keeping an eye on this so that we can make some sensible decisions as to the type of training we want to engage in in a given time period.

Illness – The safest option when you are feeling ill is to rest and focus on recovery. If you want more details about training and illness you can check out my article on whether to train when you have a cold.

It’s a good idea to regularly record these feelings (regardless of how you feel) in a training diary/app so that you can track them and correlate. So if you are off pace or your heart rate is sluggish and you have to abandon a session you can look back at your notes and see if there is a correlation. It’s also a good way to notice patterns: is it always at certain points in a week that you start to flag? could you change your weekly training routine to prevent this/put in another rest day/give yourself an extra recovery day?

4) Training Diary/Performance Management Charts

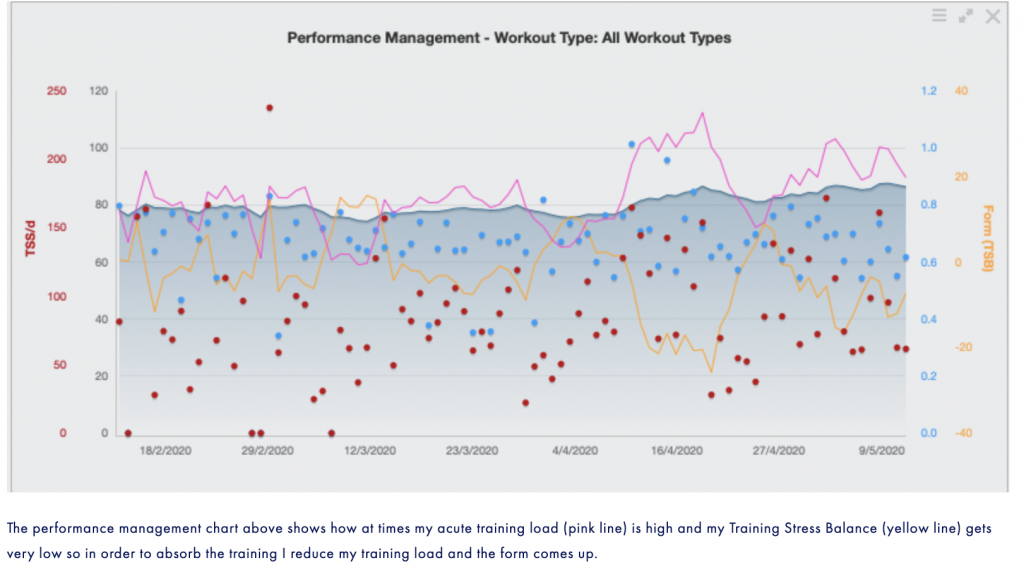

If you keep a training diary this can be a good way of tracking how much training you are doing and helping you decide whether it’s time for an easy week/few days to recover. A lot of training apps now handily correlate your training (considering both time and effort) to provide you with an overall training stress score. I like to use TrainingPeaks and the Performance Management Chart to help me track when I might need some time off, but other apps will do similar. If you are still using a more subjective version having a look at when you last had an easy few days can be a good indication (ie if it’s over 4 weeks ago, you probably need some rest!)

5) Central Nervous System Tests

Testing your Central Nervous System for fatigue is another way to identify whether or not you are too tired to train. Studies have shown a reduction in form and performance of jump tests when athletes were fatigued. There is an app that claims to measure this accurately (CNS Tap Test) by recording the number of times you can tap the required space within a few seconds. This app advises that performing the test at the same time each day can give you valuable information about fatigue using your central nervous systems response times.

Whilst fun to do this is not something that I have done consistently enough to comment on in terms of validity, but I can say that when I am fatigued from training I become less co-ordinated and sluggish in my every day movements as well as in my training. Given that heart rate variability is also measure your Nervous System response this might be seen as a more consistent and validated measure.

An approach I have used more consistently is observing my ability to perform any given session based on how my heart rate responds (if it is unusually slow to rise to an effort for example) and my ability to maintain pace (ie if I am struggling to maintain in a slow training pace) have all been signals for me to turn round go home and put my feet up.

Avoid Over-Training

Successful training isn’t just about training hard, and in fact, training too hard can be more damaging than training too little. Keeping track of things by subjective feedback and objective data as described above is a really good way of making sure that we are over-reaching enough to gain some fitness but not too much that we fall into the pit of over-training, which can take a long time to recover from.

Perhaps the most important and useful advice I have seen with regards to this is ‘if in doubt, leave it out.’ Successful endurance athletes do not, in my experience under-train, they often over-train and lose their success or never quite hit there full potential. Keeping track of things and watching out for the first signs of over-training is the best way of making sure that you will have a long and successful athletic career in whatever way you choose. The key signs to look out for are:

Unusual grumpiness/low mood

Changed and interrupted sleep patterns

Unusual thirst, especially at night

Feeling fatigued

Feeling unmotivated to train

Signs of compromised immune system (cold sores, ulcers, poor recovery from illness, frequent illness)

Unusual and inexplicable muscle soreness

Frequent injury

Loss of libido

Clumsiness

Poor co-ordination

A drop in performance

Ideally you will not experience any of these symptoms and you will manage to train wisely by:

- Sticking to the 80-20 rule (80% of your training should be very easy at a conversational pace, no more than 20% should be above this)

- Planning your training week so that you have plenty of recovery (one to three days) between your hard sessions.

- Planning your training month so that you have an easy week every third of fourth week, depending on your needs.

- Building up slowly both time on your feet and speed work. No more than 10% build per week (with no build on an easy week but significant cut back). In particular build up speed work slowly, start with one session per week then maybe progress to another slightly less onerous session in the week after you have acclimatised to the addition of the first.

If you are thinking of building up your training but are not sure where to start, why not book in for a one to one consultation with one of our coaches for some advice?

Additional questions

What should I do if I have over-trained? – Rest is the only thing you can successfully do to allow your body to recover, any exercise you do should very short and light and feel easily manageable (do not base short and light on what you could do before you got over-trained but on how you feel now).

Tags:

Mountain RunningApril 29, 2020

Comments