How do I get faster at trail running?

For a long time when I started running I just enjoyed being out and wasn’t bothered about how fast I went. However, when I started racing I realised I enjoyed the concept of pushing myself and also the process of training and seeing myself get fitter and faster.

So how do you get faster at trail running? Well, the best way at getting good trail running is to do more trail running. However, there comes a point where you don’t have any more free time to run and your body can stop responding to the same stimulus; it then becomes a bit more complex than just doing more of the same thing.

Over the years I have spent quite a lot of time reading about training methods, attending learning events, chatting to other more experienced runners, using myself as a guinea pig to practise different things and ultimately coaching professionally. Here’s some of the things I have found.

If you want to get better at running, do more running

The best way to get good at something is to practise it; running is no exception. If you run three times a week you will get fitter than if you only run two times per week. If you have been running for three weeks, you will get fitter if you carry on running for another three weeks. What seems to have the greatest effect on fitness gains is frequency; so if you run for 20 minutes 5 times per week, that’s going to get you fitter than if you run for 1 hour 40 minutes once per week.

However, a word of caution here: when I first started getting serious about running faster I went from running 4 times per week to running 6 times per week and I got very tired very quickly; I realised that I had to build up very slowly to five days then six days to avoid over-training. The golden rule is to increase by no more than 10% week by week.

Train your Aerobic Threshold

It’s really easy to think that you need to do lots of fast running to get faster; in fact the opposite of this is true. Most top athletes who train do no more than 20% of their training faster than an easy conversational pace; they do A LOT of training at an easy effort, the difference is that their easy effort is still pretty fast. How did they get fast? Well barring raw talent and genetic disposition, the main answer is that they have done a lot of training at an easy conversational effort; the more you train at this effort the faster you get for the same effort.

John has written a really detailed and informative article all about how to increase your aerobic threshold, which you can ready here.

The more training you do at this easy conversational pace, the more efficient you become and therefore the faster you become for the same effort, your aerobic threshold moves up and you have a greater endurance capacity. It is this massive endurance capacity in top athletes that supports the higher speed efforts and their overall running economy.

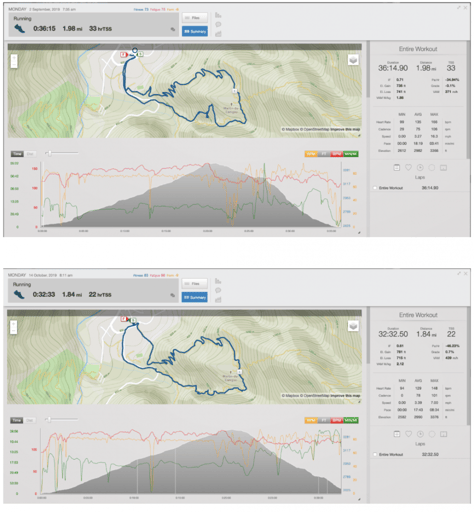

At the start of each new running season of training I have a four to eight week block of running easy; I go out and get into a good training routine but I do no speed. This usually sees me starting to get faster for the same effort pretty quickly and provides a good base for the introduction of harder sessions. You can see the improvement in the two (identical) runs opposite, in just over a month I have gained speed and actually lowered my average heart rate just by running easy!

Do some Fast Running

If you run all your runs at an easy pace you will get very good at running at that pace. Whilst you will also be capable of some faster running, your fast twitch fibres (the ones that help you run fast) will not be so well trained. To enable yourself to run faster, you need to do some faster training.

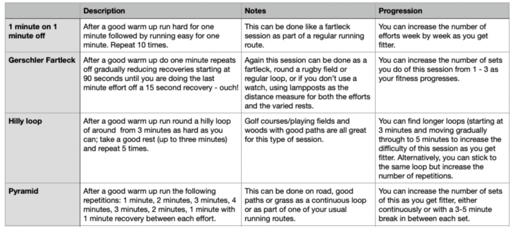

This type of training involves running at paces significantly faster than your race pace for short periods of time with some rest in between. There are many types of faster training sessions you can do and to a certain extent it really doesn’t matter too much what you do, so long as you do a small amount consistently (once or twice per week). Many people do these type of sessions on a track but I have found I get just as much training effect from running my repetitions to time around a rugby pitch, carpark, estate or on a canal bank. Doing them on grassy hilly terrain is also more like the terrain you will be racing on as a trail runner and teaches you some good motor and balance skills too…just remember not to go so fast you lose balance and fall over; you could seriously injure yourself! I tend to choose good surfaces for shorter repetitions to enable me to focus on leg speed and form and do some longer efforts on hilly loops. Here are some examples of some short interval sessions that I like to do: –

This type of training is really good for peaking (adding a bit of extra speed as you approach your key race, especially if this is a shorter event). It’s also a really good way to make some good fitness gains in a short amount of time. However, because of the intensity of the training, the body is very limited as to the amount of this type of training it can sustain. In my experience one session of this nature per week is enough, although some athletes can manage two well—spaced out (ie on Tuesdays and Saturdays).

Do some training at or around your Lactate Threshold Heart Rate.

There are many different terms of training that becomes or is contributed by your anaerobic system and they are often used interchangeably: Lactate Threshold Heart Rate, Functional Threshold Pace, VO2Max, Threshold etc. I find it helpful to think of this in terms of how long you can keep going at that pace; you can usually keep going at your Lactate Threshold Heart Rate for around 40 minutes to an hour. It usually falls to around 10 – 16km (6 – 10 mile) pace depending on how fit and fast you are; for most people it’s around 10km pace.

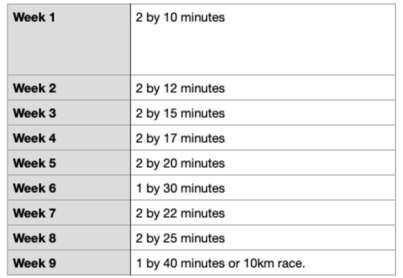

If you train at this intensity once per week, you will improve your pace at this effort (and possibly slightly increase your actual heart rate depending on how fit you are). This also makes your body more efficient at some anaerobic contribution to your running. To train in this zone, you can do longer sustained efforts of speed. A good way to progress these efforts is summarised in the table below.

Train Consistently

Another important part of getting better at something is practice, and to practise you need consistency. By it’s nature fitness takes time to build, so it’s no good thinking you can cram all your marathon training into 4 weeks; your body needs time to acclimatise and adapt to different levels of training before moving on to the next step (see about resting below).

I’ve known many people who will start their training very enthusiastically, but the regime is so onerous that they can only keep it going for a very few weeks. It’s far better to have a conservative routine that you know you can maintain for a long period of time than to start with gusto and stop after a month. If you train consistently for a period of months you will be able to see month on month how you improve by looking at things like:

How fast you can run a set distance

How your speed improves at the same heart rate/perceived effort

How much easier certain training routes become

Racing

Practise on the terrain you want to race on

Road running and trail racing are very different and require different amounts of energy and techniques. If you want to get good at trail running you will need to do some training on the trails.

In addition to this, technicality, steepness and general runnability can vary massively from trail race to trail race; it’s a good idea if you have a particular race in mind, to check out how technical the course will be and try and train either on the race course or on terrain very similar. My personal experience is that I train far better on terrain that I have trained on, so reccying a race makes a big difference to my performance; one of the first races I was lucky enough to win formed part of one of my regular training routes.

Keep easy training easy and hard training hard

Most athletes I know do their easy training too hard. The legacy of ‘no pain no gain’ is hard to drop and I have spent many nights on club ‘social’ runs watching groups of people go round the route as though they were doing their seasons’s A race.

If you’ve read anything from Stephen Seiler, you will know that his work with professional athletes reveals that they do their easy training easy and their hard training hard. This concept of polarised training is gaining popularity with good reason: it works by not over-taxing your body but allowing it enough stimulus to improve. If you don’t train easy on your easy days, you will end up falling into the den of mediocrity where all your training is neither very fast nor very slow.

It takes guts to set off on a training run with your pals and let them go, knowing you could run with them, but this is your easy day so you’re running easy. What I often say to people I work with is ‘there’s no point winning the training and losing the race’ and that is exactly what you will do if you try and do every session hard.

Do Running Drills for some Free Speed

Running drills are often thought of as the bread and butter of track runners, however, for anyone wishing for a bit of ‘free speed’ running drills can be the key, as they improve your running efficiency, making it easier for your body to run harder for the same effort. They can also be a good way of practising recruiting the right muscle groups for the job, so can form a good part of any injury prevention or rehabilitation programme. There are loads of different drills you can do and there are plenty of examples on the internet. Here is my own video showing the drills I like to do:-

Get your nutrition right

If you don’t put petrol in your car, it won’t go; if you don’t put fuel in your body it won’t go either! If you want to train right you need to eat right. This means eating enough calories to fuel your training and racing and get enough of the right vitamins and minerals to keep your body working optimally. Particularly if you are wanting to train within twelve hours of your last session, recovery food is very important, including a good mix of Carbohydrate and Protein (optimally 3:1) within half an hour of finishing a hard session can really make a difference to recovery.

It’s particularly important to maintain a healthy weight to be good at trail running so that you have a good strength to weight ratio, but also to ensure that you don’t fall into the trap of relative energy deficiency which can lead to poor running performance and injury; I have discussed this in more detail in my article about losing weight and mountain running here.

Rest

This may seem counter-intuitive but, once you have over-reached your body’s capacity to run, you need to rest to allow it to repair and come back stronger. Any type of hard training involves the break down of muscle fibres and they take time to repair and strengthen. Gaining fitness is not a linear process, but rather happens in stages with plateaus in between each increase in fitness.

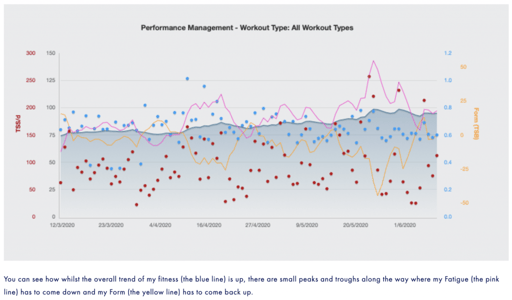

Using the TrainingPeaks Performance Management Chart (see opposite) Fitness, or perhaps more accurately Chronic Training Load actually rises slowly and in each period of recovery has to come down slightly in order to bring the Fatigue (or Acute Training Load) down and bring the Form (or Training Stress Balance) up. A lot of athletes can make the mistake of simply trying keep increasing their fitness (chronic training load) and therefore never fully recover, becoming over-trained and/or injured.

The amount of time you need to rest can vary from person to person, and also on the type of training you have done. It may take up to three days to recover from a very hard training session, for some people it may take as little as 6 hours to recovery from an easy run.

You need to find the optimum rest period for yourself. In most endurance sports, we tend have both a microcycle (of anywhere from a week to 14 days) and a mesocycle (of anywhere from 21 to 28 days).

Within your microcycle you will have a large proportion of easy training with one or two faster sessions and one or two longer (but generally easy) workouts.

Within your mesocycle you will have two or three microcycles as described above followed by a period of recovery and adaptation where you will have 5 – 7 days of very light training and more rest. This last period is important for allowing your body to adapt to the stimulations given it in the harder microcycles.

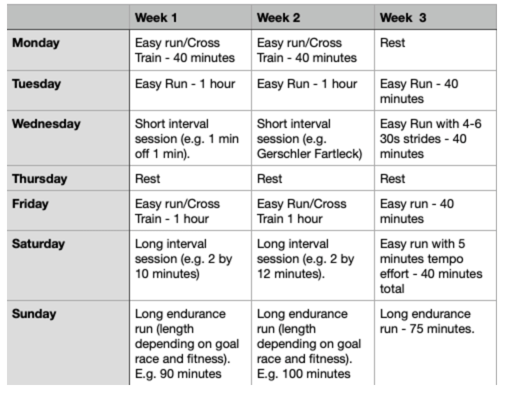

A typical mesocycle would look something like this:

Do some uphill training

If you are going to be doing trail races, you are going to have to go up some hills at some point; you might even have to go up some mountains depending on the t

ype of trail race you choose. As with everything the only way to get good at running up hill is to practise so training on some hills represent

ative of your key races is a good strategy.

Initially, just getting out and on the hills will benefit you loads in terms of psychological strength and fitness on the climbs, but as you progress you may want to include some specific up hill training.

Sessions I like to include are

- Short hill sprints – good for running strength and form – 8-12 x 20-30 second sprints on a hill with a good recovery between each effort is a great session to do for the time crunched on a lunch hour.

- Long up hill climbs – if you are planning on going up some mountains some long up hill climbs from 20 minutes to an hour at your Lactate threshold heart rate or just below is really good preparation for these types of races.

- Hill repeats with a flat sprint – this was a great session the coach at our club used to do with us involving a good two minute climb followed by a flat sprint section. This is really good preparation for races where you know you are going to come off the top of a climb to a flat section.

Do Some Races

If you want to get used to running fast for long periods of time (depending on the kind of think you like to do and your fitness levels). The best way to improve your fitness is to pick out some races you fancy, train for them and do them. Racing is a way of putting together all your hard training. A lot of people will say that they never work as hard in training as they do when they are racing; there is something about that added element of competition that enables them to push themselves further and faster.

In particular for people wanting to do a key race it’s always a good idea to do a few tester/practice races first. Some races even have acceptance criteria based on your completion of other races (e.g. Ultra Marathon de Mont Blanc).

Practice races can vary depending on your main race goal; for example if you want to run a really big ultra, it’s probably best not to do another of a similar distance shortly before, but you might want to do a marathon distance or shorter ultra a few months before to see how you go, or try an ultra one year with a view to running your best two or three years down the line. With shorter races up to around half marathon distance, it takes less time to recover from them so you can do them more frequently to test yourself for your main event. Alternatively you could do some 10-15km races as practice runs and sharpeners for you key event which may in fact be up to 25km. Equally with a marathon, you may choose to do two to three 20 – 30km races en route to your main event.

Just remember, the longer the race the longer it will take you to recover, so you will need to leave enough time between your last practise race and your key event for that season.

Listen to your body

Good runners run hard, wise runners run well. The art of being a wise runner is about balancing all the things I have discussed above and combining them with a certain amount of wisdom so that you are always working within what your body can do; over-reaching enough to make fitness gains, but not too much to injure yourself or over-train. A key component of being a wise runner is learning to listen to and interpret your body’s signals so that you know when to go hard and when to dial back and take some rest.

Having a plan of micro and mesocycles will help, but this is not fool proof, ultimately your body will tell you what it is capable of and if you listen to it you will be able to reach your full potential.

A good way to listen to your body is to spend 5 minutes each day taking note of symptoms which will help you know whether you need rest or more training. I like to use the following:

- Heart Rate Variability

- Mood/Irritability

- Tiredness

- Motivation to Train

- How the last training session went

- Stress

- Health/Illness

- Muscle Soreness

If you keep good records of these things you will start to get a sense of how your body is coping with your training regime and respond accordingly. Having a coach is a really nice way of having an extra more objective person looking at your training and well-being so you can work together to get the training just right. They usually have a wealth of experience of working with different athletes and can design a training programme suited to your individual needs and goals.

If you would like to explore the option of having a personal coach, please don’t hesitate to get in touch with us and we will be delighted to discuss things through with you and see how we can help you reach your full potential.

Additional Questions

How do I work out my Lactate Threshold Heart Rate? There are lots of different (and quite scientific) ways to do this, but I find the most user friendly are those summarised by Joel Friel in this article; this works with a seven zone system; but you can narrow it down to 5 if you wish.

What is Heart Rate Variability? Heart rate variability is the difference in time between the beats of your heart; this is a good way to assess how stressed your body is emotionally and physically. I have written more about this in my blog ‘How do I Know if I am Too Tired to Train?.’

October 29, 2019

Comments