How Fast Should I Do my Hard Efforts?

If you want to make gains in fitness and performance there is only so much you can gain from easy training in zones 1-2; at some point to continue to build fitness you may decide to introduce some harder, faster training. So how fast do you need to train?

If you are following a written plan, it should give some advice on how fast you should do the prescribed harder efforts either in the form of pace, zones or Relative Perceived Exertion. Whilst you do not have to run harder efforts at a set pace, it can be a useful way to monitor and measure improvement and may give you some indication of how to pace your A race, as well as how you might perform in it.

Here are a few things to consider when planning and doing your harder runs:

- What is the purpose of the session

- What pace you can maintain for the whole session or set

- What metric you wish to follow

What is the purpose of the session?

The purpose of the session will also dictate how fast/hard you need to go to achieve the purpose. For endurance athletes the main targeted areas in training are:

- Aerobic threshold/tempo

- Lactate Threshold/Functional Threshold Pace/Power

- Above Lactate Threshold/Functional Threshold Pace/Power

- Sprints

These targets are based on the three generally accepted and measurable fitness markers: Aerobic Threshold, Lactate Threshold (Equivalent to Functional Threshold Pace/Power), V02Max; I tend to classify sprinting a bit separately. Sessions at each of these thresholds are designed to increase the amount of time you can maintain the effort and/or increase your pace/power at that threshold, so you can go faster for a given effort/heart rate and/or maintain a particular effort/pace for longer. For sprints the aim is to improve max pace/power and your ability to recover from them. Fitness improvements at each of these zones does not work in isolation.

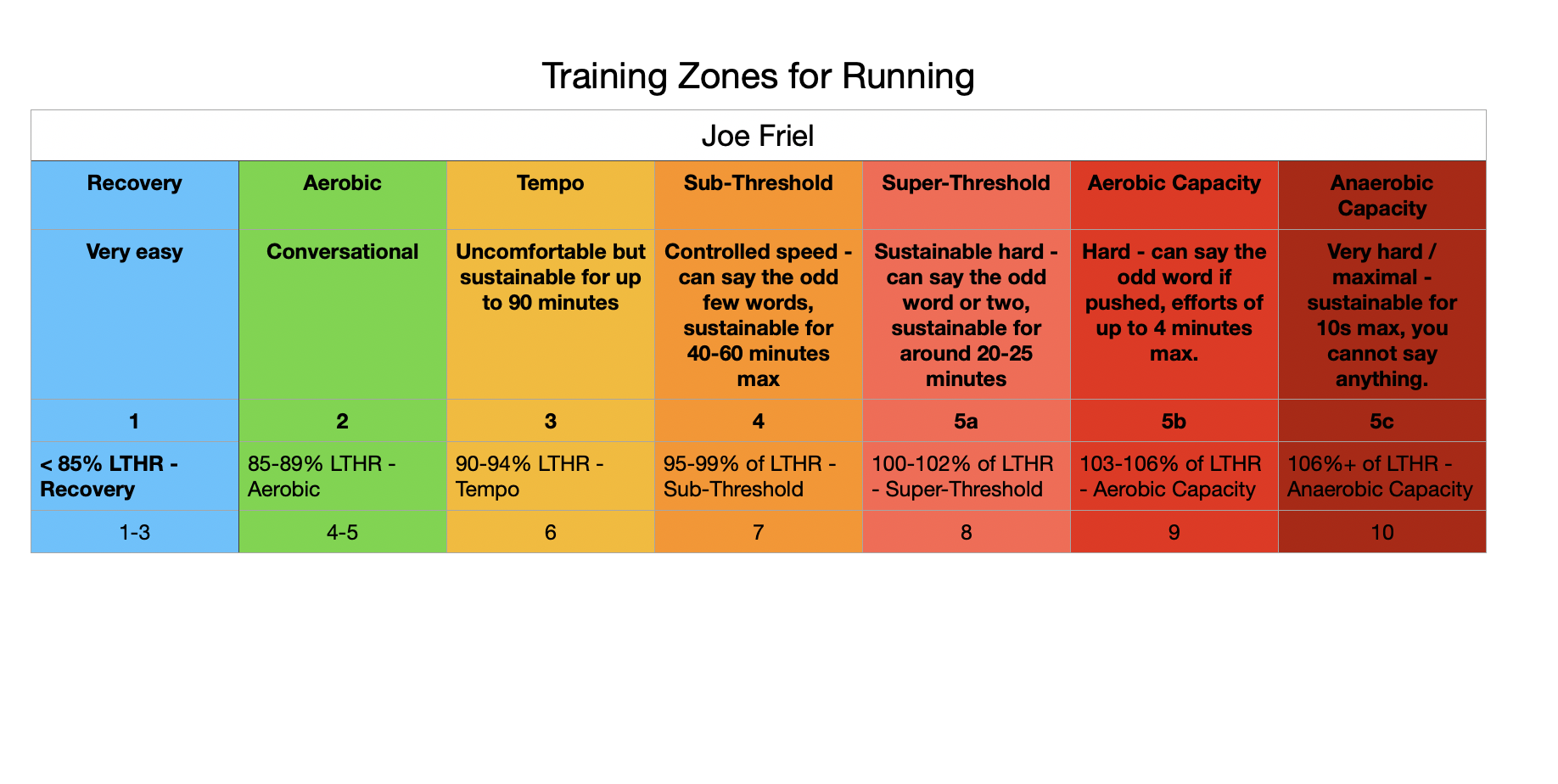

You can identify your own thresholds by getting a lab test but I have found that Joe Friel's half hour test is accurate enough for most athletes and is repeatable more frequently with less monetary expense. This way you can keep your zones up to date; I usually try to test athletes every 6-8 weeks once they are fit enough to do a meaningful test. The disadvantage of the half hour test is that it is a hard session and does assume a decent level of fitness.

Once you know what your own thresholds are and have trained in each of them regularly you will have a good idea how to pace targeted efforts for each of these workouts. The thresholds are individual to the athlete and vary according to both fitness and fatigue. For this reason you may find it more useful to work to a Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale; tests show that experienced athletes can train with accuracy at a given intensity if given a comprehensive scale to work with. I encourage athletes to cross check a given target with Rate of Perceived Exertion.

In addition to particular fitness targets, for off road events, it's important to do some training on mountainous/off road terrain. Here pace (and even power) can be so variable that it is relatively meaningless. Here in particular for longer efforts heart rate can be helpful and for shorter efforts it's best to work to Rate of Perceived Exertion. For more skills based sessions, you may find you get gradually faster throughout the session as you perfect the skill.

What Pace You can Maintain for the Whole Session or Set.

Unless instructions say otherwise the usual assumption is that you will aim to do all your efforts at around the same output (pace/power). This means that each effort will cost the same and that the power/pace is consistent throughout the effort. This often means that the first part of the session can end up feeling easier than the later part as your body builds up fatigue and your functional reserve capacity decreases.

Exceptions to this consistent power/pace are for off road efforts where some down hill/technical sections are included. As race preparation gets more specific I often like to combine different race aspects into one session rather than isolating them. So the session might comprise of some fast flat running and then after some recovery there might be an uphill 10 minute effort at Lactate Threshold. Or you might be doing fast undulating loops on the same/similar terrain to the race where you are pushing the uphill and working on fast foot work on the descents.

For running track sessions some athletes find Frank Horvill's 5 pace system is a useful way for the to pace their efforts, providing them with an indication of lap time and recovery for races from 400m to 5km. You can check out this method of pacing in John's article.

My experience is that if you wish to use some kind of pace system it works best if you use a benchmark that is familiar to you and this may depend on how long you have been running and what your main discipline has been/is.

What Metric You Wish to Follow

Training computers are brilliant devices and many offer a wide range of metrics you can check. You can plan and follow sessions set to pace, heart rate, power, Rate of Perceived Exertion and even breath rate. Most athletes use one metric for most of their workouts and stick to that. In general it doesn't matter which you choose as each has their own merits, although each also has limitations.

Heart rate - measured in beats per minute using either wrist based or a belt place around the chest or arm. This metric is great for longer efforts where the heart rate has time to respond and stabilise at a given output. However, it can mean that as you tire your pace/power drops if you follow this in isolation. Heart rate is not of much use for short efforts as it does not have time to respond so the data is not meaningful.

Power - measured in watts read by your training computer from a power meter placed on your bike/foot/chest strap. This is a great metric as it provides an instant consistent readout for uphill and flat efforts so you don't have to try and work out your target pace for a particular slope on a hill. Some running power meters are not as accurate on off road and/or soft terrain.

Rate of Perceived Exertion - a numbered scale in which the athlete allocates a number to the effort they are working at; the most well known is the Bjorg 20 point scale, but any meaningful scale will work. This is helpful as it allows the athlete to work to what they are capable on any given day, thus allowing for cumulated fatigue. It also requires no technology other than a stop watch. As with heart rate it can mean that output reduces as the athlete tires and the perceived effort at a specific power/pace increases.

Pace - measured in min/mile or min/km using your training computer which detects how fast you are going, usually using gps. This is a great way to train on even surfaces and even on tracks/routes that you know well as you know when you have done them faster or slower. It is not consistent on uneven off road terrain.

Whichever metric you use the target for the faster sections of your session should be based on your own fitness levels and ability. I tend to work this out based on an athlete's Lactate Threshold Heart Rate and/or the Functional Threshold Pace/Power. For some athletes we will also consider there 5 min maximum pace/power.

Good training plans will usually describe sessions in such a way that you are clear about what pace/effort you should be training. If it's not clear, contact your coach/the writer of the plan to be sure. I like to use the chart below, based on Joe Friel's Training Zones. This gives us a basis from which I can structure sessions and both the athlete and I know what I mean:

How accurate do I need to be?

In my experience for most things you don't need to be that accurate, so there's no point stressing too much about whether you did a rep with an average pace of 5min59s/mile (3min42s/km) or 6min/mile (3min43s/km); you will still get much the same fitness benefit. The thing I notice most is that athletes often set off too fast and either slow throughout the rep or slow throughout the set. A good strategy can be to think about the the zone you are aiming for and aim to get just inside that zone; if you manage a bit more in the later stages of a set you could see that as a bonus but know that you are creating the right stimulation once you have crossed into the zone. If you can't reach the zone, you may be too tired for the session (assuming your zones are set correctly and are up to date).

It can be worth working on this as pacing strategy and being able to pace things well is a really good skill to have when racing.

For easy sessions (zones 1-2) again it is usually better to go easier than harder, particularly if you are doing a lot of volume...many athletes do their easy sessions too hard and this compromises their hard sessions.

If you would like some personal advice on how to plan and execute your harder sessions why not book in for a 1-1 consultation? We can have a look at your training data and help you develop some harder sessions that will work for you.

Additional questions:

How do I know if my zones have changed?

The best way to know if your zones or accurate or have changed is to test; this is a good way of seeing if your training is working. Using the same route each time you do the test will ensure better accuracy and comparability.

What if I am not fit enough to do a half hour test?

At this stage in your training journey anything you do is likely to improve your fitness, even if it's all easy. That being said, if you want to do some harder work you could use a Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale for some harder efforts.

How frequently should I do my hard workouts?

Most of your training, regardless of how fit you are should be easy. Anything above your aerobic threshold is not easy and should be classed as a hard session. If you are following the polarised training approach, then you should aim for 80% of your training session to be below aerobic threshold and only 20% of your training sessions should involve training above this intensity (zone 3 or above using the Joe Friel zones discussed in this article. In practice the number of hard workouts you do can vary from athlete to athlete and even week to week for the same athlete. The best approach is to ensure that any hard session you do is good quality so one good quality hard session per week may be better than two. It's also worth noting that long endurance sessions are also classed as hard sessions, despite the pace being easy they are tiring!

When should I do my hard workouts?

The simple answer is 'when you are ready.' In practice this is not so helpful! Try to plan your workouts so that there is enough space between harder sessions for you to recover and be fresh for them; usually this means having a 48 hour gap minimum between them. If you can plan them on days with less life/work stress this will also help.

September 15, 2023

Comments